News

Ramping up accessibility

Accessibility not only is the law, it's good business. Here's how to stay legal and profit at the same time.

February 12, 2008

This article originally published in Retail Customer Experience magazine, Mar. 2008.Click hereto download a free PDF version.

|

Amy Bordogna Price is a customer-turned-employee at wheelchair-friendly Sophie's Fine Yarn Shoppe in Louisville, Ky. |

Inside, among the hundreds of balls of yarn, are wide aisles, easily accessible restrooms and movable displays. Even though the space is packed with merchandise, there still is plenty of room for her to maneuver. It's a challenge for Price to enter many stores without accommodations like those at Sophie's. A degenerative genetic condition restricts her to a motorized wheelchair.

But her experience at Sophie's always is a pleasant one. She can go into any part of the store — even the farthest corner — and not feel as if she will get stuck. Price enjoyed visiting the store so much as a customer that she applied for a job and promptly was hired by owner Barbara Franc. She now works three to four days a week as an instructor in the store.

Tim Fox hasn't found similar accommodations. As a result, he avoids retail shopping as much as possible. The wheelchair-bound attorney and co-founder of the Denver-based Fox & Robertson law firm cites the crowded chaos of the retail environment as his biggest reason for bypassing the seemingly endless rows of clothes, electronics, home products and jewelry in many stores.

He'll occasionally go to the grocery store to pick up a week's worth of food, but browsing through the clothing racks at a big box store is impossible, he says.

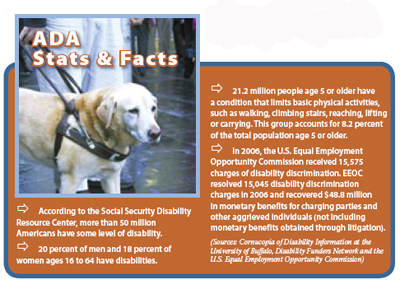

The Americans with Disabilities Act has forced many retail stores to begin making their facilities more accessible. Passed in 1990, the law is meant to ensure equality of opportunity, participation, independent living and economic self-sufficiency for disabled persons. But that doesn't mean all retail stores have complied.

The biggest problem Fox has in retail environments is navigating among the clothing racks.

"(The racks) are just so close together that you can't get through without knocking things over," he said. "A lot of the stuff people do when looking for clothes, like just simply browsing, is impossible for me to do."

Price said she stays away from stores that have lots of clutter near the front of the store, something she can see from the comfort of her automobile.

"If it's crowded at the front of the store, I will assume it's going to be crowded everywhere else," she said.

"I'm surprised that (retailers) think it's beneficial to any customer that they have all the merchandise so close together," Fox said. "I think that for mothers and fathers that have strollers it would be impossible to shop in these places."

It's the law

Retail stores fall under Title III of the ADA law, which prohibits discrimination in places of public accommodation, including retail stores. Discrimination in this instance includes both inaccessible premises and discriminatory policies.

|

Barbara Franc's (right) experience as an occupational therapist influenced her choice of building and store layout for Sophie's Fine Yarn Shoppe. |

The group's key missions include supporting the implementation and enforcement of disability nondiscrimination laws, particularly ADA, and educating public and government policy makers regarding issues affecting people with disabilities.

For retail stores, ADA compliance can entail simple things such as widening aisles so that people in wheelchairs and scooters can maneuver to the merchandise, Imparato said.

"It can be providing communication access for someone that is deaf or hard of hearing, like writing down notes to them or looking at them in the eyes so they can read lips," he said.

The whole idea is that disabled people should have access to the same merchandise that other customers have, Imparato said.

Access to justice

The Department of Justice oversees ADA, but it's impossible for it to completely monitor thousands of retail stores in the United States. So for retailers who do not abide by ADA laws, lawsuits have been the enforcement mechanism, even though many private law firms don't readily take on those types of cases, Imparato said.

"It can be hard for people who experience accessibility problems to use the legal and enforcement mechanisms to challenge the issue," he said. "I think a lot of time they just give up."

Shortly after his graduation from Stanford University's Law School, Fox began practicing general corporate law for a firm in Washington, D.C. But eventually he decided he wanted to practice law in an area that was close to his heart.

"I didn't set out to be an ADA lawyer, but, as luck has it, that's what I ended up doing," he said.

Fox teamed up with his wife, Amy Robertson, also an attorney, to form the law firm Fox & Robertson P.C. in 1996. With the goal of standing up for disabled persons in mind, their firm brought a class-action lawsuit against Kmart stores, a division of Sears Holdings Corp., in 1999. That suit argued that Kmart provided inadequate wheelchair access at its stores, something several of Fox's clients had experienced firsthand.

Before filing suit, however, Fox said they sent letters to Kmart encouraging the company to take action in its stores. Their letters were ignored, he said.

Thanks to a management change after the new millennium, however, Kmart began to heed the call for ADA compliance. Nearly seven years after the suit was filed, Kmart settled by instituting policies that would ensure disabled access to merchandise, counters, restrooms, fitting rooms and parking. Kmart agreed to limit displays stacked in aisles to grocery areas and it promised to provide a 32-inch path to at least one side of all clothing racks.

Kmart officials say it is important for all its customers to know that the company is focused on providing them with a safe and enjoyable shopping experience, said Kimberly Freely, a spokeswoman for Kmart parent, Sears Holdings Corp.

"We welcome all shoppers and associates who have special needs and strive to make shopping in our stores a positive experience," Freely said. "Ongoing improvements such as wider aisles and better inventory management will continue to make Kmart a pleasant shopping environment for all shoppers."

Freely also said that Kmart had added a "Customers with Disabilities" training program for employees. The program was designed to further sensitize store associates to the needs of various customers.

Fox said he has been pleased with the changes Kmart has made.

"Our experience with Kmart, after they had gone through a management change, they were really terrific," Fox said. "They went out of their way as much as they could to make their store a positive experience [for disabled persons]."

ADA also requires retail stores to pay attention to Web accessibility, which includes making sure a blind person could access a retail store's site with an audio reader.

In October 2007, a judge ruled that Target.com, the home page of retailer Target, must be accessible to blind people under California laws. The National Federation of the Blind had filed a class-action lawsuit in 2006 alleging that Target had failed to make its Web site accessible to the blind and then ignored the issue when confronted with complaints. According to the lawsuit, NFB's goal was to get Target.com to have its site work with screen-reading software.

Marc Maurer, NFB's president, issued a statement shortly after the decision that said, "All e-commerce businesses should take note of this decision and immediately take steps to open their doors to the blind."

Target spokeswoman Lindsey Kline declined comment for this story.

Retailers react

Thanks to her more than 20 years as an occupational therapist, Franc's yarn shop, Sophie's Fine Yarn, was built with disabled access in mind.

"It was important to take into consideration when I was designing the layout of the store," Franc said.

In addition to the layout of the store, she made sure she found a location that had a ramp for wheelchair access.

Fox said retail compliance varies by company, but it's the individual "mom-and-pop" stores that sometimes do the best job.

"When you deal with the larger companies who have a lot of resources, it's almost impossible to get some of them to make changes," he said. "You always hear how these types of law can be burdensome on mom-and-pop stores, but they really are some of the best."

Mallory Duncan, general counsel for the National Retail Federation, argues that retail stores want to serve their customers, but that determining with certainty what guidelines and standards they are supposed to follow can be frustrating.

"ADA per se is not an issue," Duncan said. "(Retailers) want to serve each and every customer."

He also said retailers face unusual circumstances when it comes to those with disabilities. For example, even if store counters are at a certain height, that height will be advantageous to some and disadvantageous to others.

"We need help from the agencies to better understand the guidelines," Duncan said.

Debate and future change?

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill already are looking to redefine the ADA law. Duncan said Congress is looking to revise the law, possibly to include labeling those who wear glasses and hearing aids as disabled. He cautioned that retailers' resources would be spread thin if the disabilities label was more broadly defined.

"If you have to make concessions to all those people, then the ones that need the most help will not get all the help they need," he said.

Duncan said many retailers already have spent significant amounts of money upgrading their stores to be ADA compliant. Revisions to ADA could require retailers to make further changes and retrofit things they already have upgraded, something retail stores are concerned about.

"The lack of certainty regarding ADA is frustrating," Duncan said. "The desire to serve the customer is overwhelming."

Fox said many retail stores are doing a better job, despite the frustration. New stores are building with ADA in mind and are widening bathrooms and adjusting counter size.

As for the attitudes of some stores, he still runs into a few that just don't care. It's important for those stores to realize a lot of people have disabilities, he said.

"Some of the best stores are out there doing their best to increase access and provide good customer service, not because of charity, but because they recognize there is a business interest in them," Fox said. "For those stores that don't know about ADA and don't cater to those with disabilities, I would say you are missing out on a profit center."

Price agrees.

"Even though I'm in a wheelchair, I still want to go shopping and I have money to spend," she said.

Patrick Avery is editor of selfserviceworld.com

Photography by David Kennedy of Pixel Photography forRetail Customer Experience magazine.