News

Culturing a customer-friendly environment

How sensitive are you to differences in ethnicity?

August 17, 2008

This article originally published in Retail Customer Experience magazine, Sep. 2008. Click here to download a free PDF version.

To someone born into another culture, something as subtle as an employee standing "too close" — or backing away if the customer is standing too close — asking a regular customer how his wife is or casually pointing to a customer to say "you're next" could cause a rift.

Subtle cultural differences between your employee and your customer can have a not-so-subtle effect. Insulted customers may tell their friends your staff is rude, disrespectful or (as is sometimes the case with cultural faux pas) bigoted, and in a moment, years of work building your store's reputation can be wasted. Meanwhile, your employee may honestly believe that the encounter went well.

An awareness of cultural differences can alert your employees to the faint clues that signal a customer is not hearing what your employee thinks he is saying. And that's vital to creating across-the-board excellence in customer experience in today's multicultural marketplace.

Don't ignore the ethnic market

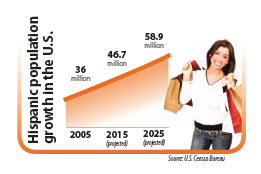

According to the Selig Center for economic Growth's "Multicultural economy 2006 Report," the U.S. Hispanic consumer market alone already is larger than the economies of all but nine countries in the world. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that the Hispanic population in 2005 was more than 36 million, and projects it will total 46.7 million in 2015 and 58.9 million in 2025.

According to the Selig Center for economic Growth's "Multicultural economy 2006 Report," the U.S. Hispanic consumer market alone already is larger than the economies of all but nine countries in the world. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that the Hispanic population in 2005 was more than 36 million, and projects it will total 46.7 million in 2015 and 58.9 million in 2025.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. The Selig Center projects that the nation's Asian buying power will more than quintuple, climbing from $117 billion in 1990 to $622 billion in 2011. That's a 434-percent gain from 1990 through 2011. The growth of Asian spending power is projected to become substantially greater than the increases in buying power projected for the U.S. as a whole, which is only 190 percent during the same period.

Many retailers that wouldn't dream of letting a market this size go overlooked in their marketing plans or product mix fail to take the cultural differences of the same market into account in the customer experience aspects of their business.

Attracting customers of another culture is more than creating the right product mix. It's also about making them feel at home during their shopping experience. From basic things such as shaking hands or making eye contact to more nuanced things such as how to address people of a different gender, a little cultural awareness can go a long way toward helping recent immigrants or visitors feel at home in your store.

"Culture alters our perception of good service," said Alexa Ronngren, author of the upcoming book "Global Guerrilla Marketing: Crossing the Cultural Divide for Greater Profitability."

Ronngren is Brazilian and has experienced that phenomenon firsthand. "When I moved to Spain, I was expecting customer service to be similar to that in Latin America: personal, friendly and very helpful," she said. "Instead, waiters would throw down the menu and stalk away. They didn't even bother to feign a smile. I thought people resented me for being [a foreigner] until I talked with a Spanish businessman, who told me that the Spanish are 'efficient in service.' They don't linger at the table. Then I realized that the service I was getting was no different than the other patrons."

Ronngren is Brazilian and has experienced that phenomenon firsthand. "When I moved to Spain, I was expecting customer service to be similar to that in Latin America: personal, friendly and very helpful," she said. "Instead, waiters would throw down the menu and stalk away. They didn't even bother to feign a smile. I thought people resented me for being [a foreigner] until I talked with a Spanish businessman, who told me that the Spanish are 'efficient in service.' They don't linger at the table. Then I realized that the service I was getting was no different than the other patrons."

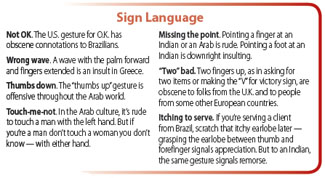

Gestures sometimes go astray

Gestures are a manners minefield. It's easy to assume that because they require no language, they are universal. Not so.

Even the smallest gestures can prove dangerously meaningful. "In Asian cultures, it is customary to lay the change down on the counter rather than placing it in the customer's hand, and Asians are less likely to make eye contact with a customer than north Americans," said David Morse, president and chief executive of new American Dimensions and author of the upcoming book "The New Morse Code: New Rules for Marketing to Race, Ethnicity, and Sexual Preference in America."

"Those things are just courtesy in an Asian culture, but to African Americans, they indicate a lack of respect. During the L.A. riots, Korean store owners in African American communities were baffled as to why their customers turned on them; cultural misunderstanding played a large role," Morse said.

"In the United States, if you want to say 'come here' using hand gestures, you put out your hand, palm up, and move your index finger in and out two or three times," said David Clark, director of the U.S. Institute of languages. "If you make the same gesture to a person from certain regions of Latin America, it can have a completely different meaning. It means that you are romantically interested and is considered a solicitation. you can imagine the trouble you could get into if you didn't know the Latin interpretation of this typical American hand gesture."

Personal space: The final frontier

North Americans tend to require more personal space than people in other cultures, but there are some exceptions. Japanese men tend to stand four or five feet apart; by contrast, North Americans generally stand two feet to three feet, or an arm's length, apart. In the Middle East, people of the same sex stand much closer to each other than north Americans and Europeans do, but people of the opposite sex stand much farther apart.

This can be a problem when an African, Latin American or Arab customer stands close to a north American store employee, who is uncomfortable with the closeness (or views it as being "in your face") and backs away. The customer may interpret the action as a rebuff.

Cross-cultural, cross-gender communications

In some cultures, manners dictate a different approach to men and women. In many cultures, it is rare (and rude) for a man to speak directly to a woman he does not know.

In some Arab cultures, it is polite to ask about someone's family, but rude to ask specifically about their wives or daughters unless you are related to them.

Yes means yes, but maybe could be no

When you mix cultures, a simple yes-no question can be anything but simple.

"Americans are a very low-context culture, so we generally say exactly what we mean by a precise choice of words," Ronngren said. "This can create challenges when dealing with people from high-context societies who use body language and other nonverbal clues in communicating, such as Arabs, Latins and Asians."

The word "no" can be a particular challenge. "Arabs generally find it rude to come out and say the word 'no,'" said Ronngren. "However, they convey it by raising their eyebrows, even while they are saying 'yes, no problem'. Asian countries also consider it rude to say no. They convey it by saying they will try their best."

"It is important not to show someone up in public in china," agreed Wendy Pease, executive director of the translation firm Rapport International. "'Perhaps' or 'I'll think about it' probably is a polite 'no.' In India, 'no' could be seen as impolite also, so 'we'll see' probably means 'no.'''

Even head shakes and nods are not entirely reliable. It is nearly universal — a nod is yes, a side-to-side shake means no. But Bulgarians and Sri Lankans nod to indicate "no" and shake their heads for "yes"; Pakistanis may shake their head to indicate they are listening (rather than disagreeing), and the Indian head bob (which to north Americans looks like yes and no at the same time) has a rich cache of meaning that is entirely dependent on context.

North Americans may find the softened "no" of other cultures deceitful or misleading, while other cultures may find our flat "no," without the softening of qualifiers or apology, harsh and rude.

Cultural competency

Social niceties are not the only differences; there can be fundamental differences in how cultures approach shopping.

Although many North Americans consider shopping a hobby, shopping in the U.S. tends to be a functional activity. But, in many other cultures, it is a social activity. entire families may shop together and selecting purchases is a collaborative process rather than an efficient one.

Cultures that have a "marketplace" shopping culture — such as in the Middle east or Latin America — expect to bargain, for example. unlike in the united States, more than 50 percent of stores in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore allow bargaining, and more than 10 percent of the stores in Latin America allow bargaining. A customer offering a price below the price marked often shocks U.S. retail employees, but haggling is standard operating procedure in other countries. The flabbergasted employee's response can be perceived by the customer as insulting.

Avoid profiling

Here's the hard part: Cultural sensitivity easily can sink into stereotyping.

Sensitivity is not as easy as handing out a cheat sheet with forbidden gestures. Consider: A gesture may be friendly in one part of Latin America and offensive in another. Do you want your employees to learn the cultural patterns of Denmark or Bolivia or the atolls of Tokelau just in case a recent immigrant or traveler from that area enters your store?

If you need a simple rule, use this one: Don't make assumptions.

It is unlikely that a young employee is going to be able to tell someone from Mexico from someone from Cuba from someone from the Philippines on sight. And it may be impossible to tell a recent immigrant from someone whose family has been here for several generations.

The answer is not to try to mimic another ethnic group's cultural differences, but to be alert to them and follow the customers' lead. understand, and train employees to understand, that people from other cultures may perceive our actions differently than intended — and vice versa. Being aware of these differences is more important that specific knowledge of cultural shopping patterns or the meaning of gestures.

Lisa Anderson Mann is a freelancer and contributor to Retail Customer Experience magazine.

ChatGPT

ChatGPT Grok

Grok Perplexity

Perplexity Claude

Claude